On June 9, 1875, in Indianapolis, Indiana, Albert L. Shelton was born, destined to be known as “The Martyr Missionary of Tibet.” His father was a carpenter by trade but when Albert was a boy of five, he settled on the plains of Kansas. The securing of the necessary water was their great problem and as soon as he was old enough to guide the oxen, he regularly made the eight mile trip to the springs with the barrels to be filled. He killed rattlesnakes with his ox-whip and coyotes with his rifle and developed into a courageous and resourceful lad.

At the age of twenty, in 1895, he entered the Kansas State Normal School, working odd jobs to pay his way. Especially proficient in mathematics, he soon took high rank in all his studies. At the outbreak of the Spanish-Cuban war, he enlisted in a college company and was sent to Camp Alger, Virginia, for training. But the Kansas volunteer did not reach the front and after a year he was back in school again. On his return he married “the girl he left behind him,” Miss Flora Beal, a fellow student at the Normal School.

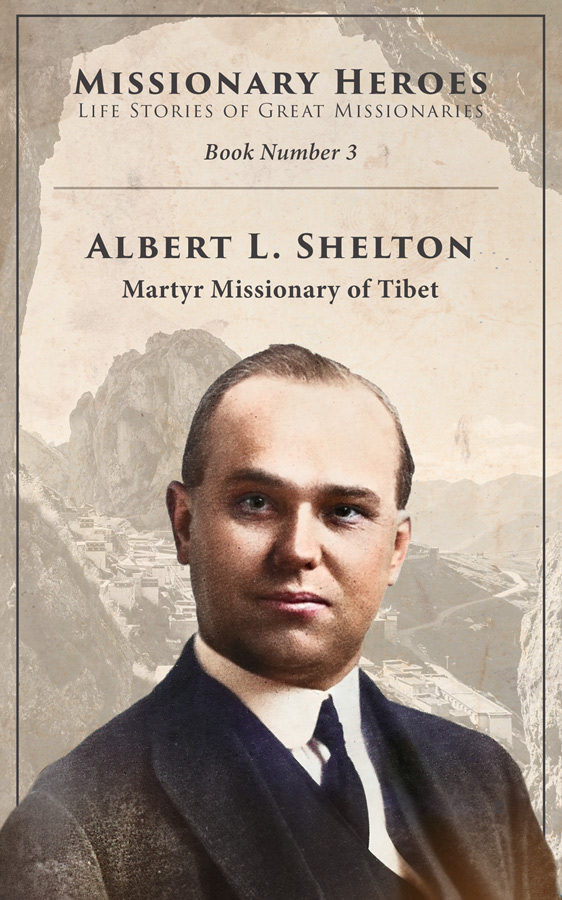

One day the President of the Normal School called him to his office and to his great surprise and joy offered him a scholarship in the Louisville Medical College. He had felt drawn to the study of medicine and upon graduating, he went to Louisville for four strenuous years of medical work. His splendid physique (he was six feet and four inches in height and weighed 270 pounds), the heritage of his boyhood on the Kansas prairies, stood him in good stead while he worked his way through medical school. Having enlisted for foreign service with the Christian Foreign Missionary Society, he was appointed upon graduation to accompany Dr. Susie C. Rijnhart, whose husband had recently died, to Taehienlu, Szechuen Province, near the border of Tibet.

In the fall of 1908, Dr. Shelton and his wife, in company with Dr. Rijnhart, sailed through the Golden Gate at San Francisco, bound for “The Roof of the World.” When they reached Shanghai, after a month on the way, they still were faced with two months of travel by river and overland before they could reach Tachienlu, a gateway to Tibet.

On March 15, 1904, they arrived at the goal—Tachienlu, which was to be their base for the next two years. The city lay in a valley cradling the Tachienlu River. Above them on either side towered the foothills of the Himalayas, the valley itself being eight thousand feet above sea level. To the west lay Tibet, the mysterious land, long closed to the Christian missionary. He at once began both the study of the language and the practice of medicine, assisting Dr. Rijnhart by taking all the operative cases. Two days after his arrival, he performed his first operation, using a barn door as an operating table.

He was confronted by the darkest medical night that can possibly be pictured. The nearest doctor was at a distance of seven days’ journey and the need was beyond description. Without the first rudiments of bodily cleanliness and lacking a knowledge of anatomy and hygiene, infection and disease had the right of way. The bitter cold and the frequent fighting developed innumerable cases of freezing and blood-poisoning. There were also a good many cases of attempted suicide with opium. All illness was attributed to evil spirits, who must be exorcized by producing a great noise and the sick man must be kept awake.

In 1906 the arrival of reinforcements in the person of J. C. Ogden and his wife, made it possible to consider the possibility of advancing into Tibet. On returning from a month’s trip to Batang, he recommended to his Board that a new station be opened at Batang. They replied with the proposal that all their work be concentrated in East China. He replied to this with words that echo the famous declaration of David Livingstone, saying: “We will go in, but not out; forward but not back.”

Upon the arrival of another physician at Tachienlu in 1908, Dr. Shelton advanced to Batang. In a short time he had opened a dispensary and soon a school was founded. Patients and pupils responded in large numbers to their opportunity. In his first serious surgical case, he saved the life of a Tibetan whose head had been crushed. The story of his success and the gratitude of the patient and of his parents sounded a trumpet for the Gospel.

Two years of furlough in the homeland, with their stress of deputation work and strain of medical research, now intervened. But Tibet called him: by 1913 he was again on “The Roof of the World.” The needed hospital building was erected and long tours were made, touching at Atuntze, Shangihen, and Derge. On these tours he was in constant conflict with the Lamas (priests) who sought to prejudice the people against the foreign doctor. They reaped a rich harvest from the sale of charm boxes, warranted to protect the wearer from disease or bullet.

He was also in constant peril from bandits, owing to the unsettled and lawless conditions that prevailed. Once, when warned not to take risks, he had replied: “It is the missionary’s duty to take the Gospel to the last man, even at the risk of his life.” When leaving for his second furlough in America and traveling under escort toward the coast in the province of Yunnan, on January 3, 1920, he was captured by bandits. The robber-chief permitted his wife and daughters to escape, holding him for “ransom.” The Bandit Chief, upon whose head was the price of $5,000, hoped to secure pardon for past offenses and the release of his imprisoned family in exchange for the foreign prisoner. Pursued by the government troops, he moved ceaselessly from place to place. In constant flight, there was little opportunity for sleep and after two months of anxiety and hardship, Dr. Shelton’s splendid physique was seriously undermined. His diary, kept on the margin of the pages of “Beside the Bonnie Brier Bush,” is one of the highly prized treasures of Christian missions. When the troops finally overtook the robbers, his guard fled and he staggered from the hiding place a free, but broken man.

Rejoining his family, he resumed the journey to the homeland, arriving in the spring of 1920. As soon as his health warranted, he underwent an operation for the removal of a small tumor. As soon as his strength returned, he was eager to be in Tibet. Before leaving Batang, he had received official permission from the Dalai Lama, the nation’s ruler, to go to Lassa. He was eager to plant the red cross banner of Christian medical ministry at the capital city itself. To a friend he said: “I am aching to get back to Tibet. I am needed more there than I am here. I can’t say that I am at home here. I know I am there.”

His daughters had reached the age when they should continue their education in America. His wife, after a trip across the Pacific with him, was to return to America to supervise the education of their daughters. He returned to Tibet alone, reaching Batang just before Christmas, 1921. Disappointed at the revoking of his official permit to enter Lassa, he started for Gartok to seek the desired permit. On the way he was shot by a bandit on February 16, 1922. Help was summoned from Batang but the wound was fatal and on February 17, 1922, the great trail breaker to Tibet passed over the Unknown Trail.